From Approvals to Access

Achieving approval for a psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) would be a significant milestone. However, given the complexities and costs associated with PATs, they won’t fit neatly into the existing healthcare system. There are a variety of challenges that will need to be addressed in order to achieve meaningful access to PATs, which will entail engaging a diverse range of stakeholders: from potential psychedelic therapists through to incumbent payors like insurance companies.

In 2022, psychedelic drug developers moved closer towards these potential approvals. As such, here we briefly tease out some of these forthcoming challenges and responses…

Part of our Year in Review series

Three Guest Contributions

We solicited three guest contributions on topics pertinent to this segment’s theme, From Approvals to Access. Each can be accessed below:

Our Analysis…

The remainder of this page features two broad areas of analysis: a look at key stakeholders in the roll-out of psychedelic-assisted therapies, and a preliminary look at the various therapy protocols and their attendant labour intensity. We finish with a brief look at the case of Spravato, which has (in some cases) struggled to achieve broad access despite approvals.

Key Stakeholders in the Roll-Out of PATs

Within the medical model, it will be necessary to communicate with, and coordinate, a range of stakeholders in the commercialisation and delivery of PATs. Examples of these stakeholders and the questions that will need to be tackled are displayed below:

Patients

Indicative Questions and Challenges: How will relevant patients be made aware of PATs as a treatment option? How might uptake be encouraged?

Potential Actions and Examples: Engage relevant patient advocacy networks.

Prescribers and Healthcare Professionals

Indicative Questions and Challenges: Similarly, how will healthcare professionals be educated on the availability of PATs, its evidence base, and what is needed to ensure they are prepared to prescribe them in appropriate cases?

Potential Actions and Examples: Traditionally the remit of medical affairs teams, such as MAPS PBC’s.

Providers / Therapists

Indicative Questions and Challenges: Is there a suitable supply of appropriately-trained facilitators for PATs? Are there adequate incentives for facilitators to (re)train in, and regularly deliver, PATs?

Potential Actions and Examples: Drug developers will adopt a “train the trainer” model to outsource the training of providers while attempting to maintain fidelity. MAPS, for example, is establishing strategic partners to support provider education (CIIS, Naropa University, Mount Sinai, etc.). COMPASS Pathways has launched centres of excellence.

See Jazz Glastra’s contribution for more.

Physical Infrastructure (e.g., clinics)

Indicative Questions and Challenges: How can suitable locations be identified, prepared and incentivised to deliver PATs, especially in the context of likely REMS?

Potential Actions and Examples: Drug developers will identify, in advance, suitable clinic networks (e.g., clinics already offering TMS, ketamine, etc.) and assist their preparation (e.g., by anticipating REMS).

COMPASS, for example, is “targeting networks of commercial treatment centers with the right infrastructure, capabilities/workforce and TRD patient mix/flow” in parallel to its Phase 3 program. This includes “evaluating offering training, site activation services and digital solutions to treatment centers”, COMPASS told Psychedelic Alpha. The company also told us that they will, “continue to seek research partnerships with treatment sites to refine our delivery model”, in advance of any product launch.

Payors and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Bodies

Indicative Questions and Challenges: How can the cost-effectiveness of PATs be demonstrated, especially given the unusual drug-assisted therapy combination? Is the requisite technical capacity in place to coordinate reimbursement, e.g., CPT codes?

Potential Actions and Examples: Drug developers engage in health economics studies and modelling in order to develop an economic case and coverage structures to present to payors and HTAs. Drug developers will attempt to engage with payors early on in the process.

MAPS PBC told Psychedelic Alpha that it has conducted extensive market research with payors and has, “consistently heard recognition of the high unmet need in PTSD” and, “positive reactions to the product profile and our data”. The company told us it has begun engagement with payors, “across both pharmacy and behavioral plans”.

Regarding CPT codes, MAPS PBC and COMPASS Pathways are working to encourage the establishment of new codes to cover the monitoring of psychedelic drug sessions1.

See Elliot Marseille, Stefano Bertozzi and James G. Kahn’s contribution for more.

Regulators

Indicative Questions and Challenges: What types of limits and guidelines might regulators such as the FDA require upon approval (e.g., REMS)?

Potential Actions and Examples: Drug developers, through discussion with regulators like FDA, will anticipate REMS programs and build appropriate services/infrastructure accordingly.

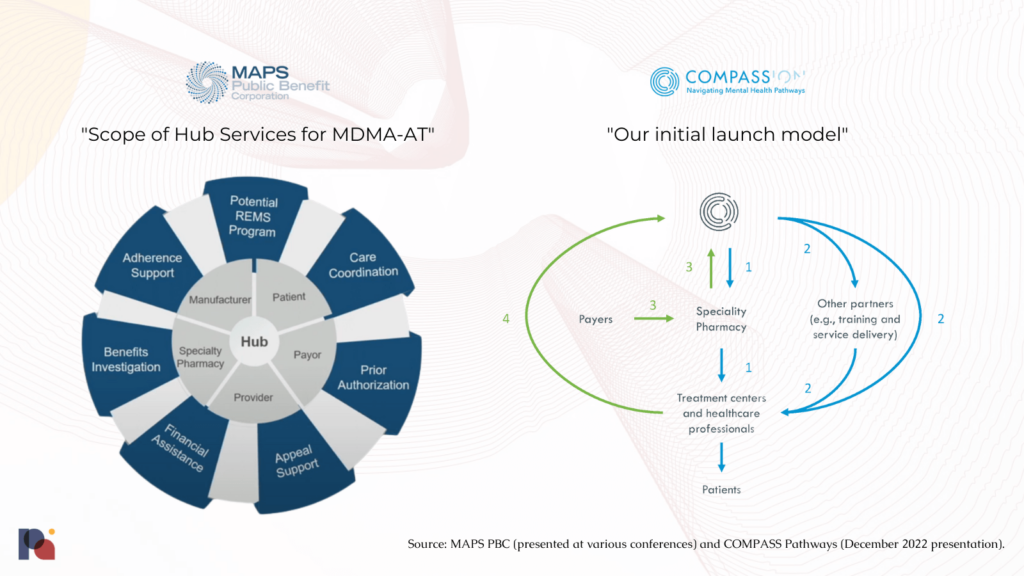

Drug Developers

Indicative Questions and Challenges: How will drug developers coordinate this complex care pathway? How involved will/can they be?

Potential Actions and Examples: MAPS PBC envisions providing “Hub Services” to provide “high-touch support through every step of [the] treatment journey”. This Patient Services Hub will coordinate “scheduling, prescription, REMS requirements, prior authorizations and more”.

See the figures below from MAPS PBC and COMPASS Pathways.

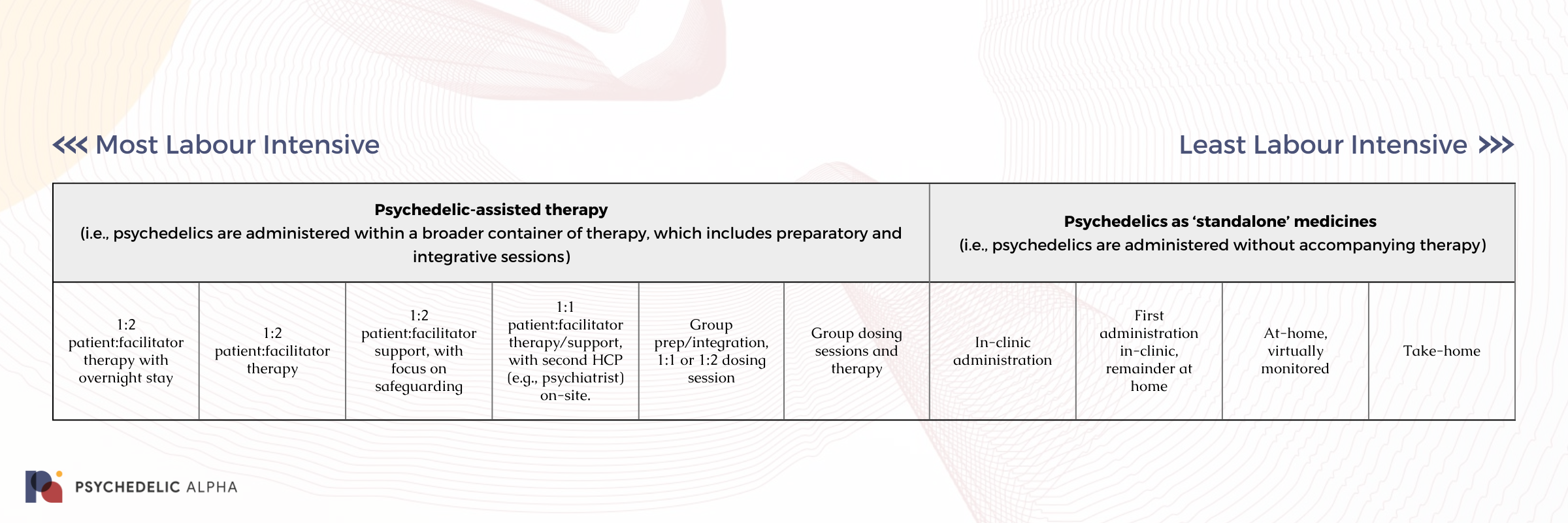

Reducing the Costs of PAT

Finding a balance between cost effectiveness on the one hand, and safety and efficacy on the other, will be crucial to achieving widespread adoption. Demonstrating rapid and durable efficacy is one way to convince payors that PATs are cost effective, while the other side of the equation is to reduce costs. Such cost reductions will largely be found in reducing the amount of labour (i.e., therapist/facilitators’ time) involved in protocols, given that this is a significant portion of cost at present.

Here, we present a very rough representation of different psychedelic medicine protocols and their attendant labour intensity, broadly speaking:

Below, we provide examples for each step of this preliminary spectrum we sketched out above.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy

(i.e., psychedelics are administered within a broader container of therapy, which includes preparatory and integrative sessions)

1:2 patient:facilitator therapy with overnight stay

Example(s): As seen in MAPS’ first Phase 3 study (MAPP1).

Notes: While FDA could require an overnight stay for those undergoing PATs (especially for longer duration psychedelics like MDMA and psilocybin), this is thought to be unlikely, given the fact that MAPS found no significant difference in safety or efficacy outcomes for those patients that stayed overnight in its trials.

Rick Doblin told us that MAPS (the non-profit) does not anticipate the FDA requiring overnight stays.

1:2 patient:facilitator therapy

Example(s): Certain MAPS Phase 3 sites allowed participants to be discharged in the evening after an MDMA session.

Notes: Drug developers like MAPS may try to reduce the number of facilitators needed per patient, and/or increase the number of patients per facilitator (e.g., by pursuing group therapy).

1:2 patient:facilitator support, with focus on safeguarding

Example(s): COMPASS’ ‘psychological support’ paradigm for its Phase 2b trial. Note that COMPASS Pathways confirmed to Psychedelic Alpha that the Phase 3 program will employ a 1:1 patient:therapist ratio, with an assisting therapist “available to support as needed”.

1:1 patient:facilitator therapy/support, with second HCP (e.g., psychiatrist) on-site.

Example(s): COMPASS Pathways’ Phase 1 study of simultaneous psilocybin administration and preparation2. As mentioned elsewhere, COMPASS Pathways’ Phase 3 program may more closely resemble this model.

Group prep/integration, 1:1 or 1:2 dosing session

Example(s):Feasibility pilot study of psilocybin-assisted therapy for demoralised AIDS survivors 3, which administered 8-10 group therapy visits and one individual psilocybin session; Sunstone Therapies’ psilocybin trial in cancer patients, who had group integration.

Group dosing sessions and therapy

Example(s):

MDMA and LSD group therapy used in clinical practice in Switzerland for trauma-related disorders4 (however, only the administration session was group, while the surrounding therapy was individual).

Maryland Haematology Oncology’s trial (a COMPASS IIT) which saw group administration with 1:1 support.

Many psychedelic retreats also employ this model.

Psychedelics as ‘standalone’ medicines

(i.e., psychedelics are administered without accompanying therapy)

In-clinic administration

Example(s): Spravato. See also a Yale study that administered DMT in a conventional healthcare setting without preparatory or integrative therapy5.

First administration in-clinic, remainder at home

Example(s):This is recommended in the label of several subcutaneous injection products, which require some education and training (during the first appointment) for the self-administration of subsequent doses.

At-home, virtually monitored

Example(s):Some online ketamine therapy providers.

Take-home

Example(s): Some at-home ketamine therapy providers. In the future, we might see psychoplastogens, microdose formulations, and drug delivery devices that allow for ‘psychedelics’ to be administered in this context.

Of course, there are other ways in which drug developers might seek to reduce costs without changing the protocol entirely. These include the introduction of technologies (from telemedicine for non-drug sessions through to fully-fledged digital therapeutics that handle preparation and integration) and, most notably, shortening the drug administration session itself by using shorter-acting molecules or drug delivery mechanisms that allow for shorter, more controlled subjective experiences6.

Of course, some drug developers are looking to skip the trip entirely in their attempts to develop non-hallucinogenic psychedelics (psychoplastogens). See our coverage of this topic in our forthcoming Research Themes segment.

Case Study: UK Agency Again Rejects Spravato Coverage in 2022

Janssen has struggled to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of its Spravato (esketamine) nasal spray to Health Technology Assessment agencies (HTAs) such as the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), who again rejected recommending it for NHS coverage in 2022.

Psychedelic drug developers should take note.

The single technology appraisal (STA) process, which was launched by NICE in 2005, is a process through which a single product, device or technology with a single indication is appraised in order for the institute to issue guidance on whether such technologies should be recommended for use in the country’s publicly-funded national health service (the NHS). Through its appraisal process, NICE “considers evidence on the health effects, costs and cost effectiveness of a health technology in comparison with current standard treatment in the NHS.”

In 2018, over a year before the European Commission (EC) approved Janssen’s Spravato (esketamine) nasal spray alongside an oral antidepressant as a treatment for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), Janssen began preliminary work as part of the UK STA for its esketamine candidate. The stated objective of the STA was to, “appraise the clinical and cost effectiveness of esketamine nasal spray within its marketing authorisation for treatment-resistant depression.”

Following Janssen’s evidence submission, NICE issued its initial draft guidance for Spravato in January 2020. Citing concerns related to the clinical efficacy and cost effectiveness of Spravato, NICE did not recommend the nasal spray for use in TRD. It would take over two years for NICE to issue its final appraisal of esketamine in 2022, at which point the institute reaffirmed its initial determination. In its guidance, NICE stated that esketamine was “unlikely to be an acceptable use of NHS resources.” While Janssen would appeal the recommendations, in its post-appeal guidance NICE once again sustained its earlier determination.

NICE’s rejection of esketamine was largely the result of “clinical uncertainties” in the evidence submitted by Janssen. Given that clinical data are foundational inputs to economic models employed by HTAs, these “uncertainties” ultimately compromised the models and their ability to reliably evaluate cost effectiveness. Amongst these evidentiary issues were the relatively short duration of Janssen’s trials of the product; the impact that the company’s positioning of Spravato as at least a fourth-line treatment had on the utility of its clinical evidence base; and, the adverse impact that Janssen’s trial exclusion criteria had on treatment translatability. While Janssen did attempt to tout Spravato’s “novel biological mechanism”, the value of this “innovative mechanism” failed to woo NICE or overcome the clinical uncertainties that were identified by the agency.

NICE further expressed its perspective that it was not methodologically appropriate to include outcomes related to societal burdens of TRD (e.g., accounting for factors like productivity loss) in the economic model. Only direct health effects and costs borne by the NHS and social services should be included in the reference case, NICE reminded the sponsor. The agency also stated that it believed Janssen failed to account for or underestimated many costs and considerations related to implementing esketamine treatments. Given that Spravato is to be used under medical supervision in appropriate treatment settings, Janssen proposed converting existing electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) suites.

However, Janssen’s plans were further complicated by the NHS efforts to integrate primary and community care for individuals with serious mental illnesses. Given the need for a psychiatric referral, Janssen’s proposed treatment delivery setting, and the extended waiting lists for primary and community care, NICE was unsure how Spravato could reliably fit into the community care paradigm it is pursuing.

In addition to these practical considerations, costs associated with these conversions, along with the costs of other requirements such as medical monitoring equipment, patient transport, and the managing of controlled drugs were not (adequately) included in the analysis, in the view of the agency. Note that Spravato requires new resources for each newly treated patient, making the costs associated with the drug’s delivery much more linear and scuppering any true economy of scale.

According to NICE doctrine, as the impact that the adoption of a new technology would have on NHS resources increases, the committee must be increasingly certain of the technology’s cost effectiveness. As a result, Janssen’s implementation plan and evidence base ultimately failed to satisfy NICE’s need for reliable and definite evidence of cost effectiveness.

However, Jannsen’s recently published Spravato data, which found the esketamine nasal spray to be more effective than Seroquel XR in a Phase 3 TRD trial, will likely encourage the company to pursue a renewed appraisal for its product. Nonetheless, for now, without public healthcare coverage, Spravato’s high costs make the treatment unaffordable for many people. As a consequence, the drug’s therapeutic reach is severely limited.

In light of similarities Spravato shares with emerging psychedelic treatments, such as the requirement for supervised administration in appropriate physical spaces and the relatively short-term nature of efficacy data, Janssen’s struggles with NICE may foreshadow hurdles that psychedelic drug developers could encounter as they move towards commercialisation.

Part of our Year in Review series

This content is part of our 2022 Year in Review, which looks back at the past year through commentary and analysis, interviews and guest contributions.

Receive New Sections in Your Inbox

To receive future sections of the Review in your inbox, join our newsletter…

- As we wrote in December, three potential new codes will be considered in February 2023 at AMA’s CPT Editorial Panel Meeting.

- Rucker et al., 2022.

- Anderson et al., 2020.

- Oehen and Gasser, 2022.

- We covered this study in more detail in a June Bulletin. Note, however, that the mere presence of HCPs with psychological expertise would likely have provided comfort to the patients.

- Indeed, the strong investor appetite for short-acting drugs like 5-MeO-DMT (as evidenced by raises from Lusaris Therapeutics, Beckley Psytech, and GH Research) is evidence of this focus on shorter trips. Beckley Psytech’s acquisition of Eleusis and its IV psilocin candidate, meanwhile, is an example of a drug delivery mechanism that might allow for a shorter subjective experience.